“E-car batteries are a key technology to implement rapid electrification of transport and achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement. Their production will generate billions of euros in revenue and create thousands of jobs. However, such positive impacts will not be realized if the value chain develops along its current trajectory, and without deliberate interventions, this growth will go hand-in-hand with a high social and environmental toll”. Almost three years after the World Economic Forum (WEF) stressed the need for a more sustainable approach, some months ago the Brussels-based NGO Environmental Coalition of Standards (ECOS) echoed its call and warned of the risk of a “pyrrhic victory”. “Cutting CO2 emissions, but creating tons of additional waste would be nonsense. For batteries to enable a transition to clean energy, we must plan for repair, reuse, and recycling right at the design stage”, said its head of energy transition, Rita Tedesco. But WEF and ECOS are far from being alone. With the huge development of the battery sector expected in the next few years, a growing number of experts have started questioning how green our batteries are.

Significant greenhouse gas emissions and relevant social and environmental risks are among the main challenges pointed out by the Global Batteries Alliance, a public-private collaboration platform, founded to help establish a sustainable battery value chain. “Production is definitively the most impactful phase of the whole value chain,” says Tedesco. “It is both very polluting and energy consuming”. Batteries are made of so-called “rare earth elements” like lithium, cobalt, and nickel that depend on mining activities, often requiring – as is the case for lithium – the use of large amounts of groundwater, which draws down its available resources for farmers and herders. Moreover, the energy used to produce the batteries accounts alone for nearly half of their environmental impact. “Even if not as much as the production, recycling is also very energy consuming and often not cost-effective. Lithium is, for instance, still quite cheap and therefore it is more convenient to mine it from scratch”, explains Tedesco. “This is also why the recycling rate of batteries is still very low.”

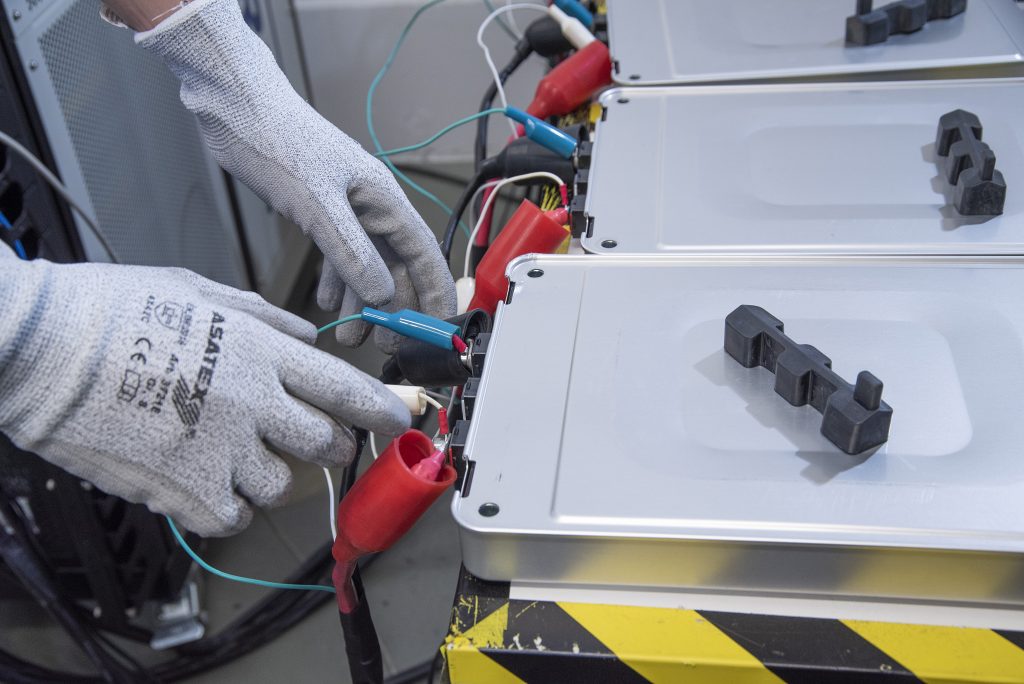

However, battery recycling is also crucial to reducing the social impact of cobalt mining. Included in the EU list of the so-called “critical raw materials”, about 70 percent of it originates today in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Demand for it is expected to increase by a factor of 4 by 2030, but its extraction in unregulated and “artisanal” mines raises grave concerns about security, respect for human rights, and child labour. Repurposing batteries to avoid both this human cost and the environmental footprint of their value chain is therefore gaining momentum. Giving a second life to exhausted batteries, otherwise mainly condemned to be landfilled or incinerated, is the core business of BeePlanet. The Spanish company repurposes batteries from electric vehicles, which are then integrated into microgrids, to optimize the use of the energy from connected solar panels, and to reduce the amount of electricity drawn from the grid.

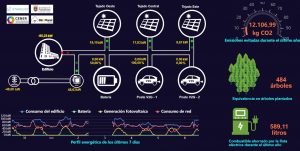

Known as V2G, the acronym for “vehicle to grid”, this technology was tested in a police building in Pamplona within the EU project Stardust. “Its car park is used by the municipality’s e-cars and since these vehicles are always out on a regular schedule, for the remaining time they can be used as additional storage,” says Carlos Larrea, BeePlanet Engineering manager. “But batteries themselves are passive systems. They just stay there, waiting for someone to tell them: ‘Charge now’ or ‘Discharge now’”. Developed by the Spanish technology centre CENER, “the brain” giving these orders is the Energy Management System (EMS). “When it detects that the cars are parked and connected to the V2G chargers, it can, for instance, decide to charge them when it’s sunny and take advantage of the solar energy production surplus, and discharge them when it rains.” All this occurs without the slightest human intervention. “The EMS reads the weather forecast for the four days ahead. Then, thanks to a smart algorithm, it calculates the best possible configuration every hour and manages the system accordingly”, explains Faisal Bouchotrouch, CENER’s technical and innovation manager. “Its latest version takes into account even more complex parameters and also adapts the energy management to the fluctuating electricity prices. By demand peaks, for example, it lowers the consumption for not critical uses and supplies the grid with solar energy. And as a result, you may even get paid for your services!”

“The configuration that we’ve tested in Pamplona within the Stardust project has allowed us to cut energy costs by up to 30 percent, but with more solar panels you can achieve even bigger savings,” says Bouchotrouch. This success has been also made possible by the surprising performances of the batteries, repurposed by BeePlanet. “We feared they would degrade much faster, but we’ve seen that they don’t,” says Larrea. “They perform much better than expected and this proves that automotive batteries can have a second life. Moreover, since they are designed for very demanding conditions, with strong consumption peaks whenever one accelerates, such use is, for them, kind of a relaxing retirement that can extend their life by 10 to 15 years.” WEF identified V2G systems among the most impactful drivers of a sustainable battery value chain and recommended that regulators incentivize them and the manufacturers, the automotive industry, and utilities work together to make them possible on a large scale.

Grid-connected batteries are expected to be the dominant flexibility and stability solution by 2030. However, the existing legislation is largely outdated and doesn’t meet the need for a sustainable approach. “Unfortunately the situation is quite simple: the only European battery directive dates back to 2006, before the ‘pre-electric era,’ and it doesn’t even contain a definition of an electric vehicle battery,” explains Tedesco. In March, the European Council adopted a general approach to revise the directive and transform it into a proper regulation, aiming at setting up a circular economy sector and targeting all stages of the life cycle of batteries, from design to waste treatment. “Negotiators could have been much more ambitious on reuse, but it’s an encouraging step forward. So far, the proposal aims at reaching 80 percent of lithium recovery by 2030, but we insist on at least 90 percent, as suggested by battery manufacturers and recyclers.” Set to replace the 2006 directive, the new EU regulation is now in its final stages and should be adopted next year.

By Diego Giuliani

Photo credits: BeePlanet and CENER